Patience has a certain impatience built into it. In Zen the word is “constancy.” Instead of patience, constancy is a kind of dedication to what you love and what you care about, and with that dedication comes a trust that by planting beautiful seeds, eventually in their own time they will bear fruit.

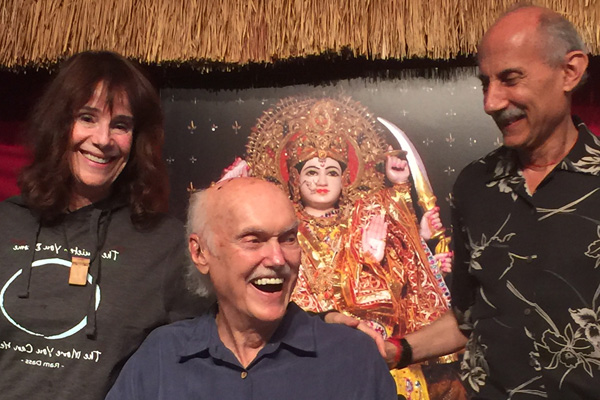

An interview by our friends at Gratitude Revealed.

Gratitude Revealed: Your words are infused into quite a few of our films, but Patience is the one I thought I’d talk to you about today.

Kornfield: In its own way, though the film was on patience, it was also on trust.

GR: Yes, exactly. You really seemed to use those two words interchangeably. In fact, it almost seemed as though you preferred the word “trust” to “patience.” Can you speak a little bit more about that?

Kornfield: A Zen master explained that patience is the wrong word, because when you’re being patient, it’s as if you’re waiting for something better to happen. Often when I’m being “patient” I’m really grasping, wanting something else. You know how kids struggle with patience . Earnest children sitting there, being “patient”, waiting for school to get out or something like that.

Patience has a certain impatience built into it. In Zen the word is “constancy.” Instead of patience, constancy is a kind of dedication to what you love and what you care about, and with that dedication comes a trust that by planting beautiful seeds, eventually in their own time they will bear fruit.

GR: I loved your point that “with patience, you’re actually bringing into being impatience.” Just by the very nature of something, you’re bringing into existence its opposite.

In the film you mentioned an analogy to surfing and the process of waiting for the waves to come. I know so many surfers speak of the meditative qualities to their relationship with water. Do you surf?

Kornfield: I don’t outer surf, no. But I inner surf. I think we are all surfers on the waves of life, the waves of gain and loss, praise and blame, success and failure, of pleasure and pain. Every human incarnation is woven from the opposites, of birth and death and joy and sorrow. So if we’re to live graciously, with a wise spirit and a loving heart, we all have to learn to surf.

That’s also why I believe that the practices of mindfulness and loving awareness have become so widespread in education, medicine and business across the country. Because they offer practical and beautiful ways, proven by neuroscience, to teach us how to surf the waves of life. They teach balance and offer ways to get back up on the board when we fall off, to surf beautifully with whatever comes to us, as best we can.

GR: I asked about surfing because I imagine sometimes the practice of mindfulness can be mistakenly seen as an intellectual, thinking process that happens only in your head. Your image is such a wonderful example of a physical embodiment of patience, or trust.

Kornfield: Wise meditation is embodied, loving awareness, attentive to the mystery of your own body and mind as it unfolds. It allows you to pay attention in a caring and deep way. This practice of presence is also an expression of innate trust or openness.

To help learn trust, picture the most trusting and steady-hearted people that you know. The ones that when you think of trust and steadiness immediately come to mind. What does it feel like to be in their presence? How do they hold themselves? When you picture or imagine or remember them, then you also remember how trust feels in yourself.

Mirror neurons help us learn from one another. The field of interpersonal neurobiology has demonstrated how we are connected in a web of being and influence the consciousness of one to another. When we evoke trust through remembering someone who exemplifies trust, we start to feel what it’s like in our own body, in our own heart. We realize, “Oh, yes. This is in me too.” We already know what trust feels like, what patience feels like, what constancy or dedication feels like. It’s beautiful.

GR: I admit, I’m experiencing that just listening to you now, actually! You have such a calm and relaxed sense of just being with the words that come out of your mouth. It is so slow and peaceful to be around you.

Kornfield: (Laughs) That’s part of my job, my profession. I’ve been teaching for 40-some years, so I’ve learned how to speak in a way that brings the inner sensibility that I’ve experienced into a shared sensibility. Now, that being said, let’s get real. If you were to talk to my daughter or my beloveds, they would tell you quite honestly that Jack can also be rather impatient. I get impatient, hurried or frustrated with things when I think they could be done better and quicker and so forth. This is really important to say, because it doesn’t help us as human beings to try to become an ideal. We’re all human. We all carry patience and impatience, dedication and apathy, care and lack of care. We all carry those noble and beautiful capacities of human beings, and we carry our failures.

Oscar Wilde called this the “tainted glory of humanity.” To understand patience or trust and other beautiful qualities is to hold them in a wide and loving heart with the fullness of our humanity. We become more patient and more trusting when we realize that trust also includes room to be impatient or to make mistakes, or to have things turn out in ways that we didn’t want or are not expected.

Then we trust something bigger. There is a famous Ojibwa Indian saying, “Sometimes I go about pitying myself, when all the while I’m being carried by great winds across the sky.” There is a vastness to life unfolding, and we are a part of it. We’re not separate from it. When we feel this, we know that we too will be carried through periods of difficulty and ease, grief and joy, loss and success, and that we’re part of something so much larger.

Our foibles and the struggles are also natural, just as we encounter rocks and obstacles rafting down a stream (or swimming up a stream if you’re a salmon). They are woven into our human incarnation. And who we are is the spirit, is the consciousness that was born into us, which is taking this amazing journey. Remembering the vastness allows for a sense of trust.

Trust also remembers that the universe is lawful. We can trust that when we plant an apple seed, we get an apple tree. When we plant a mango seed, we get a mango tree. What we plant moment by moment in all our changing seasons is what will bear fruit, in our own heart, in our relations with others and the things that we care about, and in the world.

Trust allows us to act in the world beautifully. It gives us a kind of courage, an inner strength to dedicate ourselves to what really matters, personally and globally. Trust knows that every piece adds to the whole, and every contribution of something beneficial or beautiful nudges humanity and our world in a direction that matters. This is a blessing.

GR: I’m getting this beautiful image and then there’s this character called “Fear” that sort of presents himself and tries to join the party. What would you say to this Fear?

Kornfield: Oh, I’d say, “Oh, hello Fear, is that you again? Welcome. Hello Anxiety, I see you.” Fear comes to everyone. Courage or trust isn’t a lack of fear. Fear is part of being human, wired into the deepest levels of our nervous system, in the reptilian brain, for survival. We struggle with both physical survival and emotional survival. It turns out that painful emotions light up the same areas of the brain as do physical pain. When you speak to someone who has a broken heart, their suffering, as measured in MRIs is almost identical to someone who has tremendous physical pain.

Fear is wired into us the same way. Those who are trusting and conscious have a loving or appreciative relationship to fear itself. “Oh, Fear. I know you.” You can offer it a little bow, maybe even a cup of tea, and then say, “You know, I have other things to do, so I can give you a little bit of tea, but then I’m going to focus on other things. Don’t stay around all day. Thank you.” Through the trainings of mindfulness and loving awareness, of compassion and gratitude, the trainings that now are spreading so widely, it becomes possible to acknowledge fear and not be so afraid of it.

GR: I feel like the power of this training is contagious. We are doing this with film too. By simply seeing Louie’s work visually it does have an impact. Whether we are consciously aware of it or not, it just is something that happens inside of you.

In the film, you bring us on this journey that leads us ultimately Home. From being grateful, we become gratitude itself. Was this a message you planned out and rehearsed before hand, or do you have so much trust within yourself that you’re able to just know that the words will come when you need them?

Kornfield: It’s really mysterious. I mean, where do words and ideas and images actually come from? Where does the music come from? From the fingers of the pianist and the instrument? First it arises in imagination itself. We all have access to great possibilities. We can start to trust that we are embedded in something so large and beautiful and mysterious that can display itself as music or art or love or gardening or healing or parenting or creative work. Traditionally young people would get initiated into this self respect, a communication of trust that they are carrying something of value. Each individual has this, each unique person. Your work is to offer it to the world.

My friend Malidoma Some, a West African shaman and medicine man who also has two PhDs, uses the metaphor of his Dagara people. He says, “Everyone is born with a certain cargo, and your task in this life is to deliver your cargo to the world.” To deliver what’s unique, the gifts of your incarnation. We each have them, and they can be the simplest things.

I think of the chaplain at an inner-city hospital who has a practice of twice a year of going around the hospital and blessing the hands of all those who work there. She’ll go down into the basement of the hospital and find the people who are washing the pots, and the ones who go up and clean the bathrooms and make the beds, and people who are often not recognized, along with honoring the nurses and the surgeons. She’ll take the hands of these people and bless them. Some of them say, “This is the most meaningful thing that’s happened to me this year, that someone recognizes that with these hands, I’m offering myself and something of value to the world.” It can be that simple.

GR: I’m sure you’ve been asked this before, but how would you approach someone who is maybe a little uncomfortable with the idea of meditation?

Kornfield: I don’t use the word “meditation” if that triggers someone’s fears or makes them uncomfortable. I speak of ability to listen deeply to themselves and to listen deeply to their connection with the world. I would explain that modern neuroscience shows how we can learn to steady our attention, quiet our minds, open our hearts in a systematic way. Simple practices of mindfulness, gratitude and compassion positively affect our health and well-being, and beneficially affect all those that we touch. To me, this is what’s important, not whether someone calls it “meditation.” These human capacities are shared by everyone. One of the great heritages of humanity is that cultures and elders across the world have taught us ways to be more fully present for one another, attend more deeply and with more caring to our own heart and to those around us.

GR: Beautifully said. Thank you. I was wondering about the soldier on the battlefield who is going to feel exponentially and justifiably impatient? “Yeah, yeah, yeah. Gotta go. Gotta go.” Do you have an idea of how we can introduce meditation to that environment?

Kornfield: I’ve been an advisor to an organization founded by Liz Stanley and Amishi Jha that has been training Army and Marines in mindfulness and steadiness and equanimity pre-deployment. When we send a young person who is 18 or 19 years old to a distant country, such as Iraq or Afghanistan, where the culture is completely unfamiliar to them and then put heavy weapons in their hands, we want them to be inwardly prepared. By training them in advance in mindfulness, inner balance and equanimity, there is a steadiness that comes from that training. By training them to regulate and steady their attention, they are less likely to react and harm others and harm themselves out of an unconscious fear. They’re able to see more clearly.

With this training, when they return from their tour of duty they’re also less likely to carry a high level of trauma. Because they’ve learned the skills of mindful attention and self-regulation, this allows for inner processing of experience and healing in ways that would not have been known to them. It can make a huge difference to them, and reduce the unnecessary violence and reactivity.

GR: I’m so excited to share that. Thank you. Is there anything else that you’d like to say about Patience and Trust?

Kornfield: I would love to add that the work Louie does is so effective because he uses remarkable images from the natural world. He reminds us that we’re embedded in a grand blossoming of life force on earth, and that we’re part of it. My teachers in the forest monasteries of Southeast Asia said that when people lose their way, bring them back to the natural world and teach them the practices of love, and then they’ll find themselves again. I see Louie doing that for millions of us.